I’ve been doing a lot of freewriting lately, taking inspiration from creativity teachers like Natalie Goldberg, Julia Cameron, and Lynda Barry (Lynda Barry! is! amazing!).

The idea is that you sit down with some blank pages in front of you and just start writing, either for a set amount of time (10 or 15 minutes) or until you’ve filled up a certain number of pages (2 or 3).

Don’t worry about what’s coming out; just focus on writing words. Or, if you get stuck, you can do some doodling and just enjoy the way the lines spill out of your pen onto the page.

The important thing is to keep the pen moving.

Freewriting is a fabulous exercise for unlocking your inner creativity.

It’s also pretty much the opposite of how you want to start with a collaborative team writing project — unless your goal is to spark maximum creativity. In that case, give everyone on your team some blank paper and some pens, and free up an hour for them to start scribbling ideas.

This is not a bad idea, actually, and more corporations should consider creativity workshops like this instead of trying to figure out what formula will let them use AI to produce as much cookie-cutter SEO content as possible without human intervention.

(Prediction: Within the coming year, AI content will be so generic and ubiquitous that we’ll start prizing actual stories from actual human beings. We will crave human connection amid the coming flood of AI-powered bullshit, and the real human voices will — I hope — stand out like lighthouses on a foggy night.

If you want the help of an experienced journalist and storyteller so that you can be the lighthouse instead of the fog, let’s talk.)

That said, most content projects don’t aim at stimulating wild creativity but at producing a specific deliverable: A blog post, a byline, a white paper, or an e-book.

When kicking off a writing project like this, it's beneficial for everyone to agree on a few key things:

- what we’re doing

- when it’s due

- why we’re doing it

Such alignment is as necessary for a small project like a short blog post as it is for something big like an annual report.

But that doesn’t mean content teams always do this. I've worked on plenty of projects that started without a clear idea of what we were doing. It inevitably leads to wasted work and confusion down the line.

Client: "We need a byline on topic X. We'll put our CTO's name on it."

Me: "Great. When is it due, and what's the goal?"

Client: "It's an open deadline, but we'd like it by the end of next week. The goal? We need some media hits, but we don’t have any news to announce, so the goal is to publish this byline.”

Me: “Okay …”

Two or three weeks later, we’ve created a draft, and we're deep in revisions when it suddenly emerges that the CTO has different priorities or that the client has decided to focus on a more urgent press release. The draft is put on the back burner. A month after that, the client returns their attention to the piece but decides to rework it so they can attribute it to the CMO instead. Someone else, from the CMO's team, starts editing the draft and wonders what the hell this is and who produced this, because it doesn't align with anything the CMO talks about.

Sigh.

These kinds of direction changes happen all the time — and part of writing as a content team means being flexible enough to roll with the changes that are an inevitable part of organizational life.

However, having goals spelled out at the start provides a framework that will make everyone's life slightly saner.

Two tools can help you get closer to sane in your content projects: A project kickoff meeting and a well-structured assignment brief.

The kickoff meeting

For small projects like a short blog post or social post, you can align on objectives through a simple conversation with your client. As informal as this conversation may be, it's helpful to record the decisions somehow — which will take you straight to the next section on creating an assignment brief.

A side note: When I write “client” here, I’m referring to the consumer of the content team’s work product, whether that’s an internal client, like your boss or a team over in marketing that has requested your team’s help, or an external client that’s paying your firm for services.

Holding a kickoff meeting with the client is extremely helpful for bigger projects like a research report or a lengthy e-book. It doesn’t have to be long, complicated, or formal, although it might need some of these attributes for complex projects or large teams.

At its simplest, the meeting will benefit from having a straightforward agenda:

- Establish the objective (or objectives) for the content project

- Decide who is going to do what (roles and responsibilities)

- Set a deadline, or multiple deadlines, if there are several key milestones that the team needs to hit

- Agree on other crucial parameters for the content product itself, such as word length and tone

- Identify any additional assets that the final product might require, like photos, illustrations, or a call to action with a trackable link

- Agree on the medium for communicating and taking notes so that everyone can stay on the same page throughout the project.

Walk through the agenda and make the decisions. You can use this kickoff meeting template if you want something to start with. (I started with a “meeting notes” template from Google, made some tweaks, and added an agenda for a basic content kickoff meeting.)

The assignment brief

In advertising and design, the “creative brief” is a core document that establishes what the client wants, the design parameters, the story the team is trying to convey, how it will be used, and so on.

An assignment brief is the same idea, but for written copy: It’s a document that specifies what we’re trying to produce. It gives the writer or content team clear directions on what they need to write.

An assignment brief can be formal, with a template and multiple boxes that someone needs to fill out before the writing can begin. However, it can also be as simple as a Google document with a short paragraph describing the assignment.

The degree of formality you’ll need will vary depending on your organization. Larger organizations with more complicated review processes and many stakeholders will likely benefit from an assignment template that spells out what the content team needs to deliver optimal results. A more informal assignment brief may be sufficient for smaller organizations or small content teams with good working relationships established with the internal customers of their content production.

Whatever form the brief takes, it’s indispensable to have something concrete that all stakeholders can refer to when creating, revising, and finalizing the content product.

If your clients don’t give you an assignment brief or are reluctant to work with you on creating one, don’t push it — make it for yourself instead. The idea here is not to force clients to fill out a form before working with you, but rather to create some structure for a conversation with the client. So, if you don’t like the idea of showing a brief to your client, set up a conversation instead. Ask them questions about what they want, and use their answers to fill out the brief as you listen to their responses.

It’s useful for the brief to include a few key elements:

- Working title

- Short description of the content you’re going to create

- Purpose/goal of the piece

- Expected word count

- Target publication date

- Target publication channel (website, news site, social network, etc)

- Production timeline with key milestones

- Team members responsible for this assignment

- Supporting notes and links to resources

That last piece is crucial. The more resources the assignment brief contains, the more valuable it will be to the writing and editing team. But you don’t have to add everything all at once.

A brief often starts with a working title and a simple one-paragraph abstract. As the team discovers more details about the assignment, and as they do research, they can add notes and links to the document. Eventually, it may even include the outline created in the next major step of the process — and at that point, the assignment brief has become a comprehensive resource for creating the content, a one-stop shop for kicking off, writing, and reviewing the draft. In this way, the assignment brief serves a dual purpose: It’s got the assignment at the top, but it’s also the shared notes document, with all relevant notes and links below.

It’s helpful if your assignment brief lives in a cloud-based, online document system, such as Google Docs, so the team can update it and add to it as the project evolves.

A shared cloud document is not always possible, for instance when you are working with clients who want to receive Word documents attached to emails. In such cases, it’s okay for the assignment brief to be less dynamic. If you are in a situation where you need to get executive sign-off, having a static document can serve as a kind of permanent record.

I’m sharing a simple version of an assignment brief template that you can use for your content projects. Please let me know if this helps you!

Flexibility and EQ

I got some feedback after my last newsletter that I was giving away too much of the store by sharing my whole process, and I’ll probably hear that about these templates now, too. Maybe I am, but I don’t think so.

With editorial work, templates are helpful — and I hope the ones I’m sharing help you — but they’re not the whole story. Sometimes, you can put a lot of work into creating the ideal, efficient processes with perfectly tuned templates for every step of the journey, only to find that no one is using them. Sometimes, a complicated or cumbersome template becomes its own undoing. Sometimes, people just need handholding!

That’s one of many reasons that team writing projects require a fair amount of emotional intelligence, flexibility, and willingness to listen.

The collaborative writing series

Recommendation

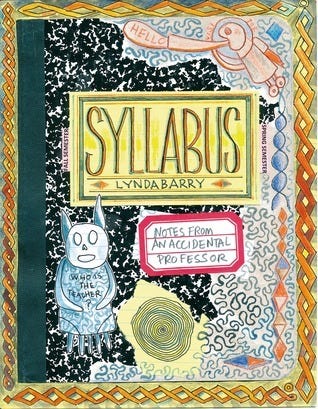

As I mentioned above, I’m loving Lynda Barry’s work right now. Her books What It Is (from 2008) and Syllabus (2014) are just amazing. My local library categorizes them as graphic novels and filed them in the Young Adults section, but they’re neither novels nor YA. What they are: Instruction books on writing and creativity, wrapped up in an some really personal reflections and memories from Barry’s childhood, woven through with philosophical reflections on memory, creativity, and what Barry calls “the image” (a particularly “alive” kind of memory or appearance). They’ve also got incredibly charming drawings of octopi, monkeys, cats, and cute kids on nearly every page. Deep, provocative, entertaining, troubling, and useful.