This summer, I took a five-week course from The Good Listening Project to learn the craft of listening poetry: poetry that arises from deep listening in a one-on-one conversation.

A listener poet is someone who spends time with you, maybe twenty minutes, and then writes a poem for you about whatever is on your mind or in your heart.

But couldn’t ChatGPT just do that?

If the only thing you want is a middling-quality poem, then sure. But if you value human connection, then no.

Asking a chatbot to listen to you may be therapeutic for some, and the AI can generate poems of a certain sort. But using AI in this way not only misunderstands what AI is good for, it also misses the point of deep listening. It’s like playing a video game when you feel lonely instead of calling up a friend – it might distract you, but it won't address the basic issue.

If you’re looking for the validation that comes from being seen and heard, then you need someone to talk to. That’s where listening poetry comes in. It’s not just about producing a poem. It’s about the spark of connection, the alchemy of hearts and minds meeting. It’s about being heard and seen by another human being.

TGLP is a nonprofit that works with hospitals and other healthcare organizations to reduce stress, anxiety, and burnout, and to increase human connection, using the tools of listening and poetry. The organization has been doing listener poet sessions since 2018 at places like Sibley Memorial Hospital at Johns Hopkins, the Mayo Clinic, and Harvard Medical School’s Center for Primary Care. TGLP works with doctors, nurses, residents, medical students, patients, and family members, all to help people feel heard.

As soon as I heard about this practice, I had to learn more. I’ve been a listener and a poet my whole life, and these modes of being have played significant roles in my career. Being an active listener made me a better journalist, communicator, and leader. Being a poet (even a shy one, of “Barefoot Rank”) has helped me stay attuned to the power and dynamism of language, and it’s made me a better writer and editor. Listening has been an increasingly important part of my spiritual practice in the past decade.

That I'd eventually bring deep listening and poetry together might seem inevitable, at least to those who know me well. But it took me a while to get here. I’ve talked about taking my typewriter to street fairs and writing poems for passersby — a similar discipline, but in a faster, less intimate setting that felt intimidating for a newcomer to street performance — but haven’t done typewriter poems for anyone outside of my family. TGLP provided a context that felt right to me.

The course was a profound experience. Over five weeks in June, ten of us came together twice a week, for three hours each time. Our cohort included a wide range of amazing and talented individuals with deep experience across both poetry and healthcare. Our instructor, Ravenna Raven, led the course with dedication, enthusiasm, expertise, and a terrific sense of emotional availability and vulnerability. She created a welcoming, nurturing, exciting space for learning.

The Good Listening Project is currently accepting applications for Cohort 12 of its Certified Listener Poet training program. Click the button below to find out more!

We studied poetic techniques, listening skills, how to hold space, trauma-informed practices, crisis management skills, how to connect across difference, and more. We heard from guest speakers, all of them experienced listener poets, who inspired us with stories of healing and writing. We practiced listening to and writing poems for each other and for one remarkable guest, a neurologist with a love of poetry that he longed to share with his patients.

And then, during the course of July, we did a practicum: Each of us held six listening poetry sessions and wrote six poems for six different individuals. I had the honor of spending time with eight amazing “poemees” and writing poems for them (I did two extra because of scheduling complications). It gave me a window into the worlds of those I listened to, and a deeper understanding of what it means to be a therapist, a doctor, a nurse, a chaplain, or just a human being dealing with change, pain, and complexity. And they told me that the poems they received were moving, inspiring, and encouraging.

As for the course's impact on me, reading Robert Pinsky’s The Sounds of Poetry and Singing School and James Longenbach’s The Art of the Poetic Line sparked a personal renaissance in how I approach the music and meter of the mostly free verse I write. Learning how to distill interview notes into poems was the transformative practice I was looking for. I know how to hold a conversation, form a connection, and draw people out: I’ve practiced this for years. Now I can use those skills to write poems for them in addition to bylines.

As a listener poet, I can use my journalistic and poetic skills together in the service of helping people feel heard and helping them express deep emotions and experiences. Like other listener poets, I can bring gifts of presence and poetry to those who need them. (Please read my fellow listener poet Rebecca Wilson's piece, Good listening on the backstairs, for a beautiful expression of that aspiration.)

To borrow a term from fellow listener poet Elizabeth Torres, aka Madam Neverstop, I look forward to offering poetic consultations, in person or via phone/video, to anyone who feels the need of connection and a poem.

As a ghostwriter, speechwriter, and communications strategist, I can use the listening skills I honed and refined in this course to continue helping leaders discover what they truly want to communicate and what form best suits their stories.

As a poet, I have shelves of notebooks I’ve kept over decades, and suddenly they look to me like a rich compost pile, ready to help grow new poems from my own experiences.

And finally, as the coach and facilitator of writing circles and workshops, I’m looking forward to weaving these practices into events I have coming up later this year.

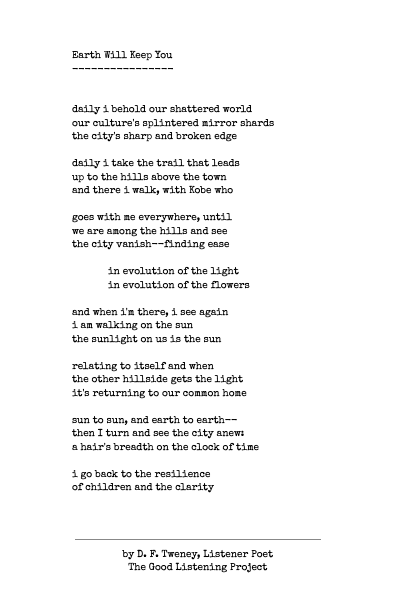

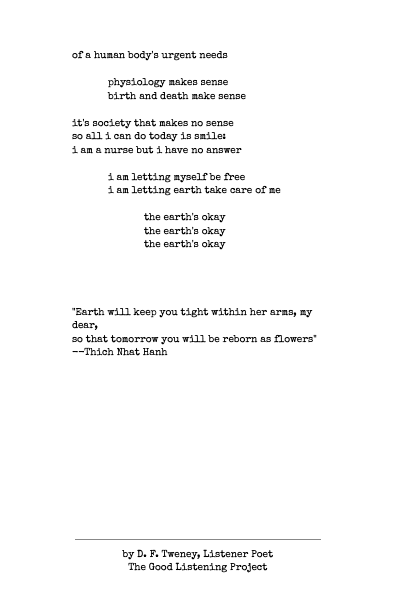

I’ll close with a poem that I wrote during the practicum.

Earth Will Keep You

The origin story for this poem: He is a nurse, husband, and "dog ownee" who works two days a week for an organization providing care to the chronically homeless, and two days a week in a pediatric intensive care unit. Most of his thirty-year nursing career has been in ICUs. Before that, he ran the family ranch for fifteen years. He was drawn to nursing work by a strong sense of duty, motivated by his family's history of military service. "I became a nurse so I could be a soldier without killing things," he says. He finds the work with the homeless is so frustrating – there is so much care they need that he's unable to provide – that he feels the PICU is a place of refuge. He knows exactly what he needs to do there. And there are compensations to working in pediatrics. Recently, he was walking around with a 12-year-old patient with Downs syndrome who had come into the hospital very sick, but who got much better. She was cheerfully asking everyone's names and middle names. "Kids are so resilient," he says, "so you get that payoff. It rejuvenates you."