Around the turn of the century, people started talking about the “attention economy.” A natural outgrowth of the ad-supported Web, this stemmed from the idea that people’s time and attention would soon be valuable commodities, because of their scarcity.

The phrase has dwindled in popularity but the concept remains. And now it’s not just ad-supported websites that are competing for your attention: It’s apps and operating systems too.

In this world, regaining control of your own attention may be a radical act.

In fact attention is probably more elastic than people initially thought it was. But it is limited, and the odds of your attention being hooked by an advertisement declines as the world gets more saturated with commercial messages of various kinds. The most obvious rational response by any advertiser is to increase the wattage of their messages in hopes of standing out from the crowd, which is how we got to an internet filled with autoplaying videos, animated corncobs selling mortgages, and “You won’t believe what these child stars look like today.” The past ten years’ evolution of ad-supported Web sites — and apps — have shown that there’s virtually no limit to what companies will do to try to snag some fragment of our attention.

But as the tech world started going mobile, from 2008 on, the battle for your attention started getting baked into the very interfaces of the software we use. And this is where things get a little creepy.

The field of persuasive design, also known as coercive design, appears to have emerged from the free-to-play (F2P) games industry, where the object (from the game designer’s point of view) is getting you hooked to the point where you are willing to fork over money in order to continue to play. I learned about this from a couple of amazing posts in 2013 by game developer Ramin Shokrizade, one on systems of control in F2P and another very provocative post on coercive monetization. These posts are fascinating for the light they shed on how games like Candy Crush Saga or Puzzles and Dragons get you hooked on emotional rewards, then entice you to pay a little bit of money (preferably using some sort of fake currency), knowing that once you’ve paid a little bit you’re far likelier to pay lots of cash and become the sort of “whale” that these game developers rely on for their profits.

But such design techniques are actually much older. Slot machines use intermittent, variable rewards to maximize their addictive potential, a technique discovered decades ago by behavioral psychologists like B.F. Skinner.

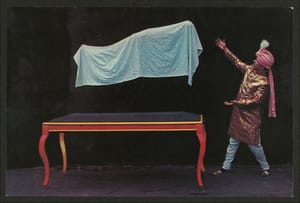

And magicians have been exploiting perceptual and cognitive weaknesses for even longer than that.

“Magicians start by looking for blind spots, edges, vulnerabilities and limits of people’s perception, so they can influence what people do without them even realizing it,” writes Tristan Harris, a magician and former “design ethicist” at Google, in an essay that lays out some of the ways software design makes use of attentional weaknesses. Harris details a few common techniques. Some of them might seem straightforward, like the way menus control your choices, concealing what’s not listed on the menu. Others are more subtle, like the way social media app notifications exploit our desire for social approval and our sense of obligation to reciprocate. For these apps, interrupting you and taking up your time is actually good for their business.

I might add that there’s another trade which takes advantage of attentional misdirection: Pickpocketing. This New Yorker story about pickpocket Apollo Robbins is an good way to gain appreciation for how pickpockets work. It’s less about sleight of hand or delicacy of touch, and more about getting you to focus on someplace other than where the action is. Plus, the story has a great lede, describing how Robbins picked the ink cartridge out of Penn Jillette’s pen.

You can spend an enjoyable hour on YouTube watching videos of master pickpockets in action.

After you’ve done that, spend a little time with the apps you use most and see if you can figure out how they’re redirecting your attention, and why.

Top image source: NYPL Digital Collections