Quirky might seem like one of the more extreme examples of Silicon Valley excess in recent years, but its recent pivot — and the way its CEO handled it — is a rare example of honesty and transparency.

The startup’s premise was inspired, if a little idealistic: Take inventors’ half-baked ideas, help them turn those ideas into legitimate products, then sell those products in stores, sharing profits with the inventors.

The company raised over $185 million over the course of its six-year life. But the most successful inventions it has turned out are frankly underwhelming. The “Pivot Power Strip,” which allows its plugs to rotate so it’s easier to plug in several bulky “wall wart” adapters, and the “Bandit,” a line of rubber bands with little hooks attached, like mini-bungee cords. In other words, useful stuff, but hardly high tech.

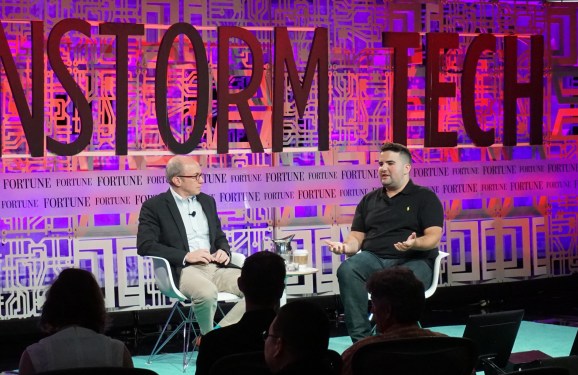

So, in classic Silicon Valley fashion, the company is pivoting to something new. Founder and chief executive Ben Kaufman described that new path with unusual candor and humor earlier this week at Fortune Brainstorm Tech, an elite conference in Aspen, Colorado that I was fortunate to attend.

Kaufman was funny, blunt, self-deprecating, and pulled no punches. In short, he stood out in the crowd: You rarely, if ever, see entrepreneurs acting humble or self-deprecating onstage in Silicon Valley events.

At this point, Quirky has burned through almost all of its $185 million. Asked when the company runs out of money, Kaufman quipped, “Weeks ago.”

“I hope we raise more money,” he said — though he was silent on who the company would raise it from, or whether the company’s previous investors would pour more capital into the company. (Probably not.)

So Kaufman is counting on a two-pronged strategy to bring Quirky back from the brink. He seemed well aware that it was a long shot, but it’s also clear he hasn’t given up on the company at all.

The first part of Quirky’s new strategy is predicated on forming partnerships with big manufacturers, like GE, who can bring Quirky’s products to the market.

Kaufman acknowledged that selling products in “big box” retailers wasn’t generating enough profit to keep the company afloat. Yes, he said, the products’ sales generated a small margin for the company — they were profitable, strictly speaking. But add in Quirky’s quite substantial overhead expenses, and the company was losing money.

Plus, he said, the brand worked fine for things like power strips and power-cord management gadgets, but it didn’t work so well for more expensive products, like the connected air conditioner Quirky made together with GE.

“People don’t want a ‘quirky’ air conditioner, they want a good one,” Kaufman said, to laughter from the audience.

The partnership with GE makes Quirky into an ideas shop — an invention factory — for the bigger company, which has deeper pockets and more manufacturing resources, not to mention better relationships with those retailers who are so critical to the consumer products category.

The second part of the new strategy, Kaufman said, is Wink, Quirky’s platform for connected home devices. With many companies now betting that the Internet of Things (IoT) is about to take off, what’s needed is a common communications standard to help devices talk to one another and communicate with the Internet. Wink provides that, through a single app that you can run on your phone or a wall-mounted tablet.

Products that work with Wink include GE’s connected “smart” LED light bulbs, Schlage smart locks, the Nest thermostat, and more. Kaufman says more than 300,000 homes already have Wink-compatible devices inside them, which is a substantial base, and that Wink will do $25 million in revenue in its first year.

“On a clean sheet of paper, that would be an incredibly huge startup,” Kaufman said. “The problem is that its attachment to Quirky has plagued it.”

Quirky certainly lived up to its name over the years. Kaufman chuckled over an $80 “connected egg tray” that he was very excited about: When you were running low on eggs, it could notify you and order more from the grocery delivery service, I suppose.

“Obviously it didn’t sell that well,” Kaufman acknowledged. But, he said, it was meant more as a demonstration of what could be done with a connected home, rather than a moneymaking product in its own right.

In the end, I’m not certain whether Kaufman’s onstage appearance in front of a bunch of high-powered investors and executives did his company more harm or good. He certainly didn’t duck from the responsibility of having failed, and having lost a lot of investors’ money.

But if anything will save Quirky, it will be that transparency. Kaufman said that he told the community about Quirky’s new direction back in February, and that while they weren’t excited about it, most of the community members were understanding and supportive. The company is still getting thousands of new product ideas submitted every week, and that’s due in large part to the fact, he says, that people still trust Quirky.

“We have to be authentic because all we have is the community’s trust in us,” Kaufman said. “The reason people trust us is because we’ve never hidden anything, from our community or from our partners.”

In a year when everyone talks about “transparency” but few actually practice it, that’s an admirable stance. I wish Quirky — and Ben Kaufman — the best of luck.